I was starting to feel the onset of the usual depression setting in when the last orchids of the year disappear in the Midwest, sometime in October. So when a long weekend was coming up for me the second week of October I looked at orchid observations on iNaturalist and decided to drive south and treat myself to a new orchid or two and maybe lift my spirits a bit.

Scanning through October observations I found out about a really cool orchid which I had no idea even existed, Ponthieva racemosa (or "Hairy Shadow Witch").

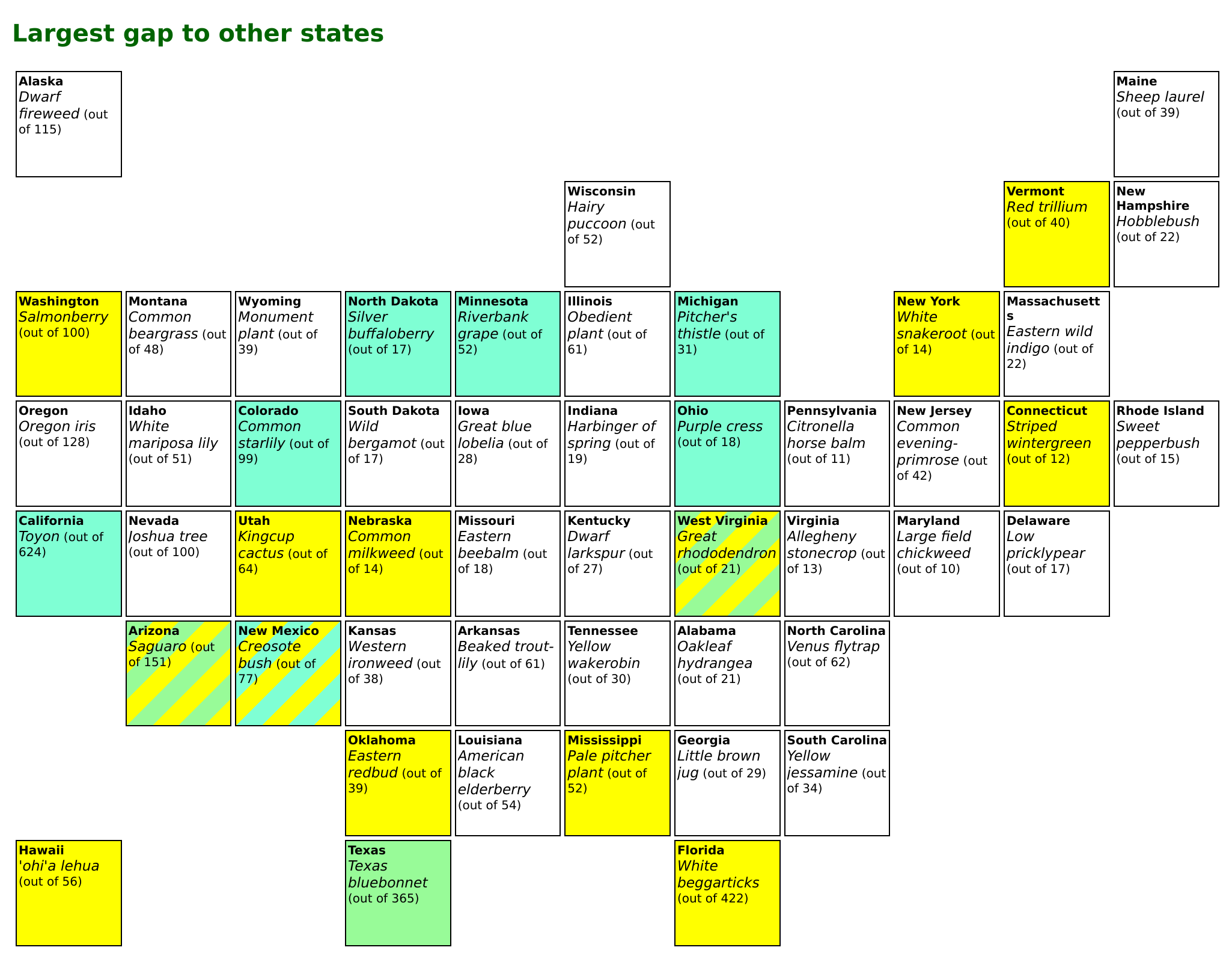

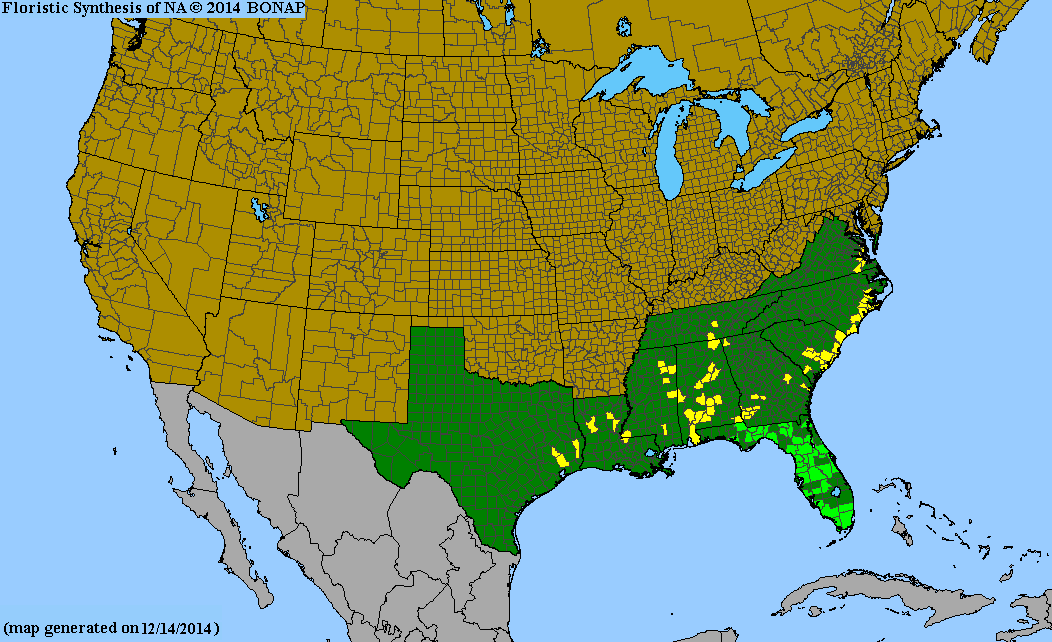

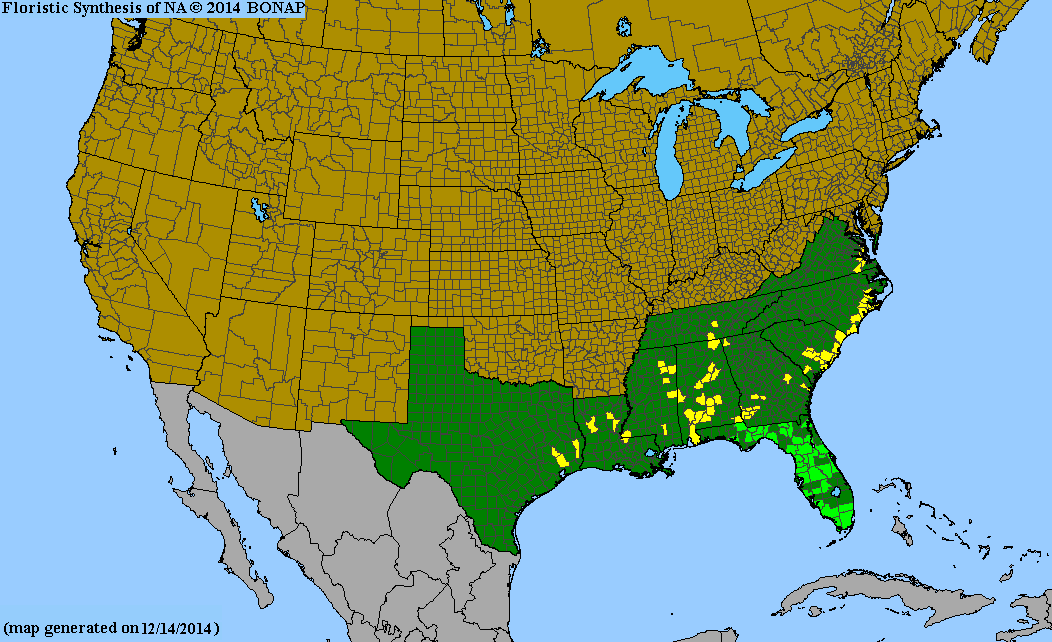

BONAP distribution map for Ponthieva

The closest locations in Tennessee and Virginia both looked to be about 8 hour drives from Columbus, OH. And while it would mean a lot of driving it did not look impossible for a 3-day weekend. I decided I'd prefer the ones along the coast in Virginia since I've never been to the East Coast and I'd have a chance to also find Spiranthes odorata (or even Spiranthes bightensis) that way, other species I had never seen before.

The next step was to find as many pictures of Ponthieva as I could. iNaturalist observations proved not very useful for planning as the taxon is obscured everywhere, so the only information for any observation was the month, but not which day (or even week) of the month. But looking at pictures outside of iNaturalist I noticed that a lot of the pictures from Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina were from mid to late September and I started worrying that I would drive that far just to find flowers already done the second week of October. After a while I noticed that a lot of the pictures I was looking at were taken by the same photographer, Jim Fowler. He found them in South Carolina over several consecutive years, and dates ranged from about first week to third week of October, with the first week pictures having a lot of buds at the top still and third week ones with bottom flowers done and only some flowers left at the top. So now I really wanted to go to that same spot in SC since I had a good chance of them being in full bloom in the second week of October.

Going to Charleston, SC however is an almost 10 hour drive from Columbus, OH - definitely not possible to go there and back when also considering gas and bathroom breaks. I had not taken any vacation yet this year and so asked if I could take the remaining 4 days off that week at work, even if at rather short notice - and I could. So now I would have plenty of time to get there and even stop at some other locations along the way.

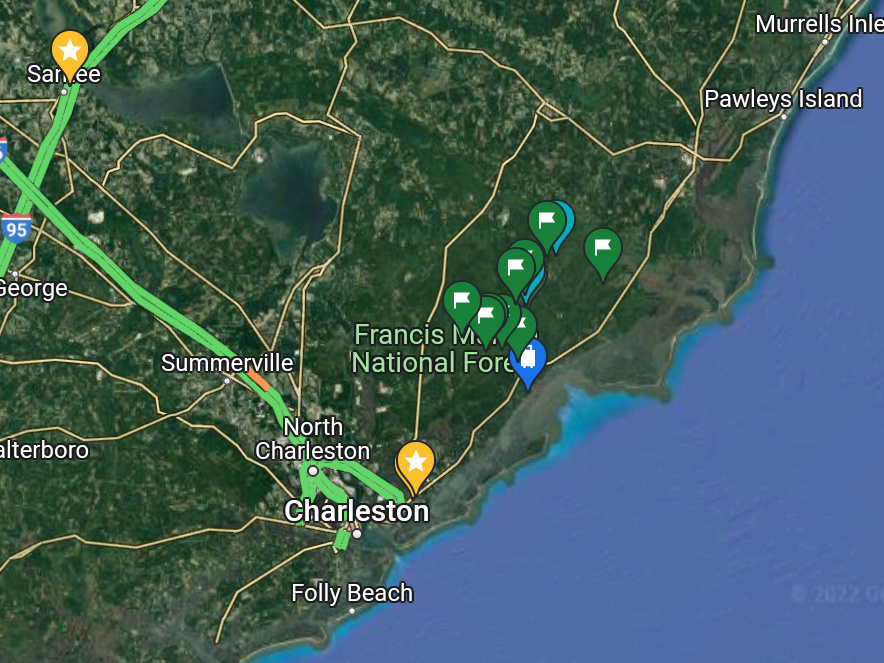

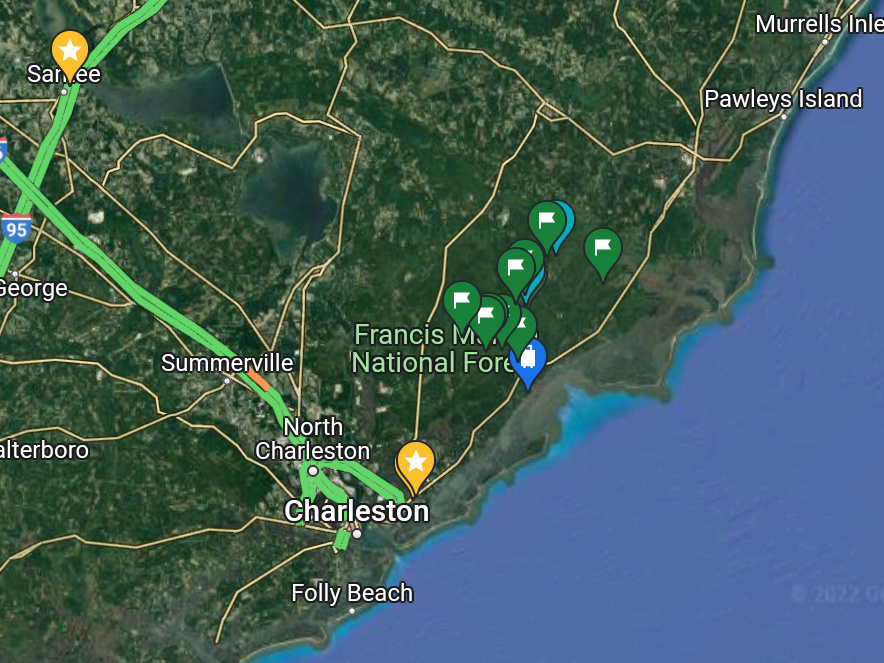

My markers on all the dirt roads criss-crossig Francis Marion

Over the next days I further studied all the inat observations of Ponthieva in SC to see where people might have found them. No exact locations of course, but everything pointed to Francis Marion National Forest, which is also where Jim Fowler had photographed his. In his blog posts he mentioned that they would grow along the dirt roads throughout the swamp forest. In fact the forest service he said, way back when building those roads through the swamp, used sand which contained a lot of crushed sea shells, which in turn created the ideal habitat for orchids. So they would actually grow right on the embankments of those forest roads.

I worried a bit about not being able to drive the dirt roads, hurricane Ian had just swept through the area and I only have a normal car, no truck or 4WD. Also, while those blog posts had some location description ("dirt road off Halfway Creek Road, close to the Santee river") it was by no means an exact location. And he mentioned that they can be hard to see (which, having see them now I would disagree with). He also said that there would be 1000ds of flowers along those roads. I'm quite good on my feet and not afraid to walk a few miles, so I felt if I couldn't drive the roads I would walk them, and in that case I would not likely miss the flowers. And if need be I could now spend two entire days just searching for them, walking a bit along every single forest road if I had to!

My car and a Ponthieva

I took the above picture right after I arrived in the evening - I took a short detour along Halfway Creek Road (a big paved road through Francis Marion) on the way to my motel for the night and just wanted to get an idea of the condition of the dirt roads, so I could make a battle plan for the next two days. The first dirt road I turned into was in perfect condition (much better than any in Ohio) and, not really having expected to already find one the day of my arrival, the orchids were growing right on the road and not hard to see at all. In fact they were much taller and showier than I had expected.

Most of the orchids were not right on the road but under the ferns on the embankments

That is not to say that I would have been likely to just find them without knowing where to look from the earlier research. The one right on the flat surface of the road was the exception - a lot of them liked to hide under ferns on the side of the road instead. When I explored more over the next two days I also found them trailing off into the swampy parts of the forest at times, away from the road. As is often the case with rare flowers, they can be locally abundant - this one definitely seems to like Francis Marion forest a lot. I found them on four different dirt roads, separated by several miles and each about a quarter of a mile long, and each comprising 100ds of plants.

Unlike with many orchid flowers, the lip is at the top with Ponthieva

Om nom nom (not sure this is an actual pollinator for it, but it certainly liked the nectar)

Jim Fowler's blog also mentioned finding Epidendrum conopseum, the Greenfly Orchid, growing on an oak tree in a 1700s churchyard. I googled for 1700s churches in South Carolina and realized there is only 3 or 4, one of them in the middle of Francis Marion forest and only reachable via a long dirt road. That had to be it and I could just put it in Google maps! So while not equipped for taking pictures of something high up in a tree, I got a picture that's at least identifiable, and the only epiphytic orchid I have ever seen.

Epiphytic orchids grow on tree bark

One thing to mention is, you should not be like me and blindly trust your GPS - instead double check the route first. It took me over 90 minutes to reach the church from the spot I was at, blindly following Google maps navigation, but only 18 minutes back. Turns out for some reason Google had me go along 8 miles or so of a dirt road, just to loop around at the very end and then go almost 7 miles back on the same road before turning right. Apparently it though you can't make left turns off this (one lane!) dirt road. Luckily I was not on a tight schedule and could still enjoy driving through the forest (twice!) and I even spotted a bald eagle flying in front of my car on the way to the church.

The biggest adventure of the trip was a Habenaria repens I spotted in the distance the next day, in the shallow water of a forest pond. There was a strange log swimming in the deeper water close to it though, and after staring at it for several minutes it moved a bit. And I realized it was an alligator! I come from Ohio where there is no dangerous animals in the forest (except for humans and ticks), so that was a bit of a shock and sent me running away. After much contemplation I decided against walking close to the orchid, even though I'm still disappointed that I was so close to it but then couldn't get a good picture.

I think this was a Waterspider orchid in the distance, but unfortunately it was being guarded

I also saw countless other lifers (176 according to the inat calendar). Two favorites are a sundew species I had never seen before, Drosera capilaris (Pink Sundew) and a plant I had no idea even existed, Burmannia biflora (Northern Bluethread). The Burmannia genus used to be in an order called "Orchidales" before DNA testing revealed it's not really an orchid at all.

Two favorite lifers, Drosera capilaris and Burmannia biflora

Lastly, on the way to Francis Marion I also stopped in Congaree National Park, and was extremely lucky to find 1000ds of Spiranthes odorata (Fragrant Ladies Tresses) in full bloom there. Hard to compare or find even higher superlatives when seeing so many incredible things, but this might actually be the biggest highlight of my entire trip, considering Spiranthes are my favorite flowers and this species was also a lifer for me.

Spiranthes odorata - despite its name I didn't notice any smell