PhyscoHunt 2021 summary: what have we learned so far?

Dear PhyscoHunters,

Starting in 2018 we have requested your cooperation in our goblet moss hunt and finally we are ready to share some of the results and findings that you all have contributed to gather. During the past months, the members of the team at UCONN and Texas Tech have been receiving your samples, vouchered them, cultured the spores when possible, and compared their genetic variation to determine their ancestry. Let us begin by emphasizing that the contribution of many iNaturalist users and the members of the PhyscoHunt initiative have made a difference. Your participation has increased the amount and the diversity of the data we have analyzed and we are sincerely thankful for your time!

Quick background recap

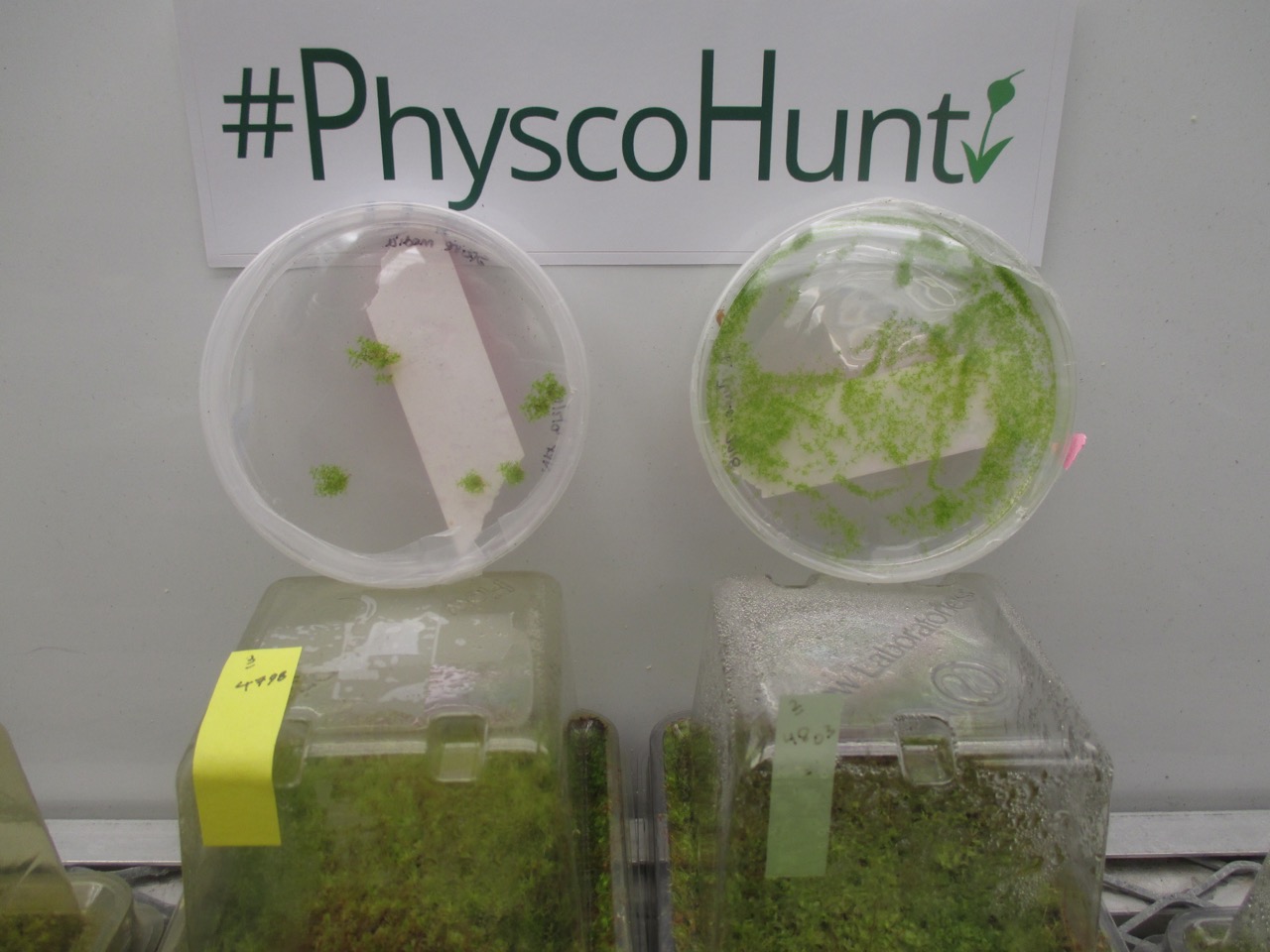

Our original aim with this project was to identify genetic variation within the goblet moss, Physcomitrium pyriforme in North America an Europe and, in particular, whether polyploidization (shifts in genome size) played an important role in the origin and diversification of this moss. We chose it as a model organism because moss evolution is relatively little known in the broader context of plant science, and a strong influence in polyploidization was suspected. The main questions we were posing, however, are not only relevant to a tiny moss, but they also enrich our general knowledge on how plants (all of them, including the tiny ones) evolve. Physcomitrium has as a couple of extra advantages: it can be cultured in lab conditions, so even with a small sample of viable spores, we can, potentially, produce a large amount of tissue to generate genomic libraries. The last final advantage of this choice is its wide range and collection easiness, particularly in Eastern North America. That's why we asked for your help!

Your contributions

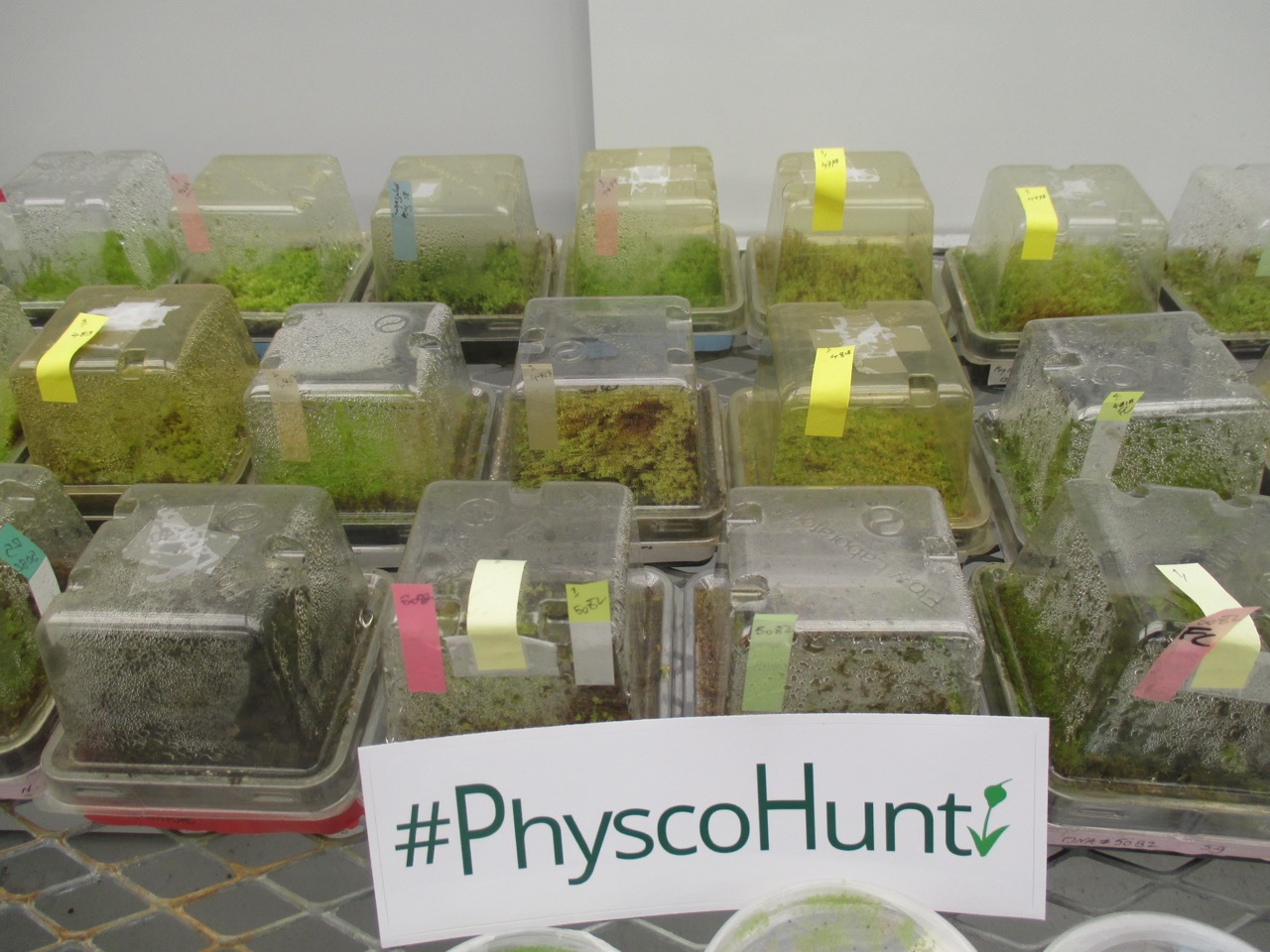

PhyscoHunt was active mostly from 2018 to 2020 (although we are still happy to receive Pacific or European samples!). During this period of time more than a hundred iNaturalist profiles joined the project to stay in touch and receive updates. We are delighted to see that enthusiasm for a tiny moss! We monitored all the new Physcomitrium observations that popped up, especially during spring time of the past seasons, and tried to contact the user that had found goblet moss. If you are reading this, chances are that we requested your help after we saw one of these observations.

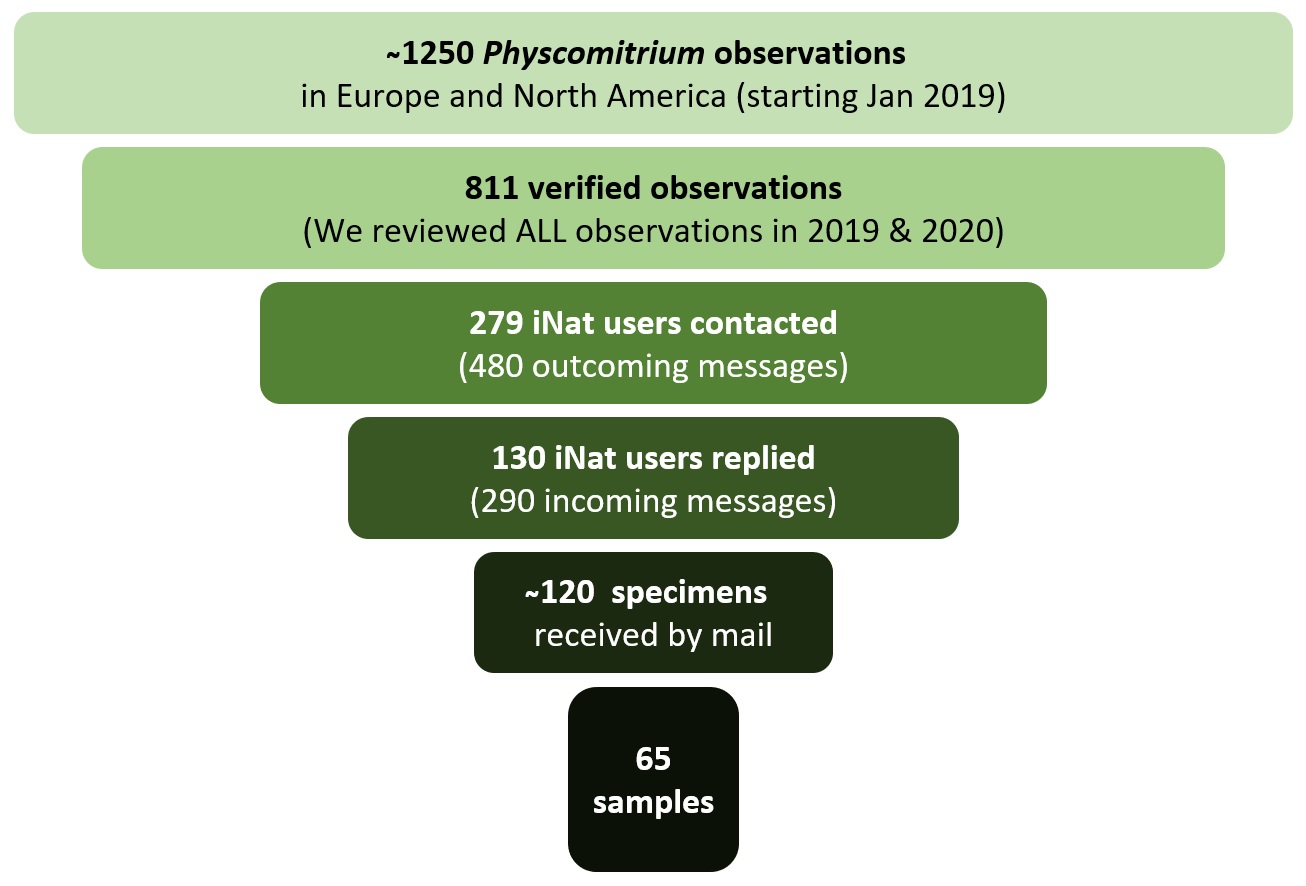

Overview of the PhyscoHunt sample gathering figures

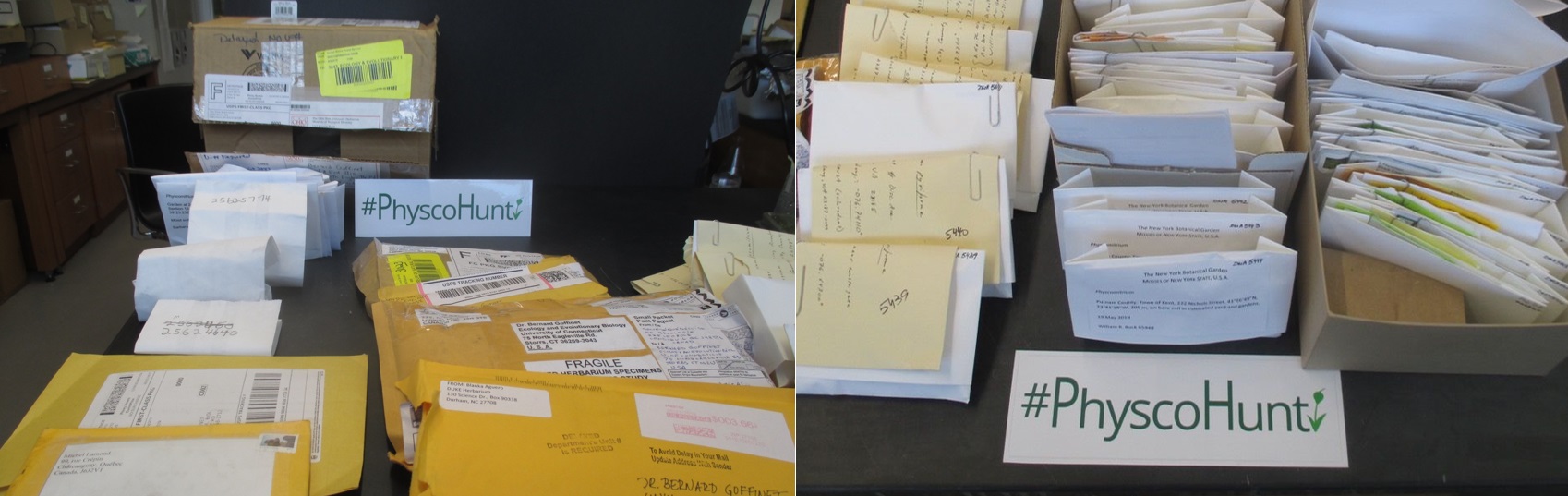

All in all, we attempted to contact the observers of over 800 Physco observations, corresponding to a total of 279 iNat profiles. We received an answer from 130 of these profiles, and for many of them, this was the beginning of the hunt. Sometimes the collection of the sample was not possible, but often our most committed Physcohunters would return to the right location, monitor the colonies until the capsules were ripe, or look further for new samples in the whereabouts of the location.

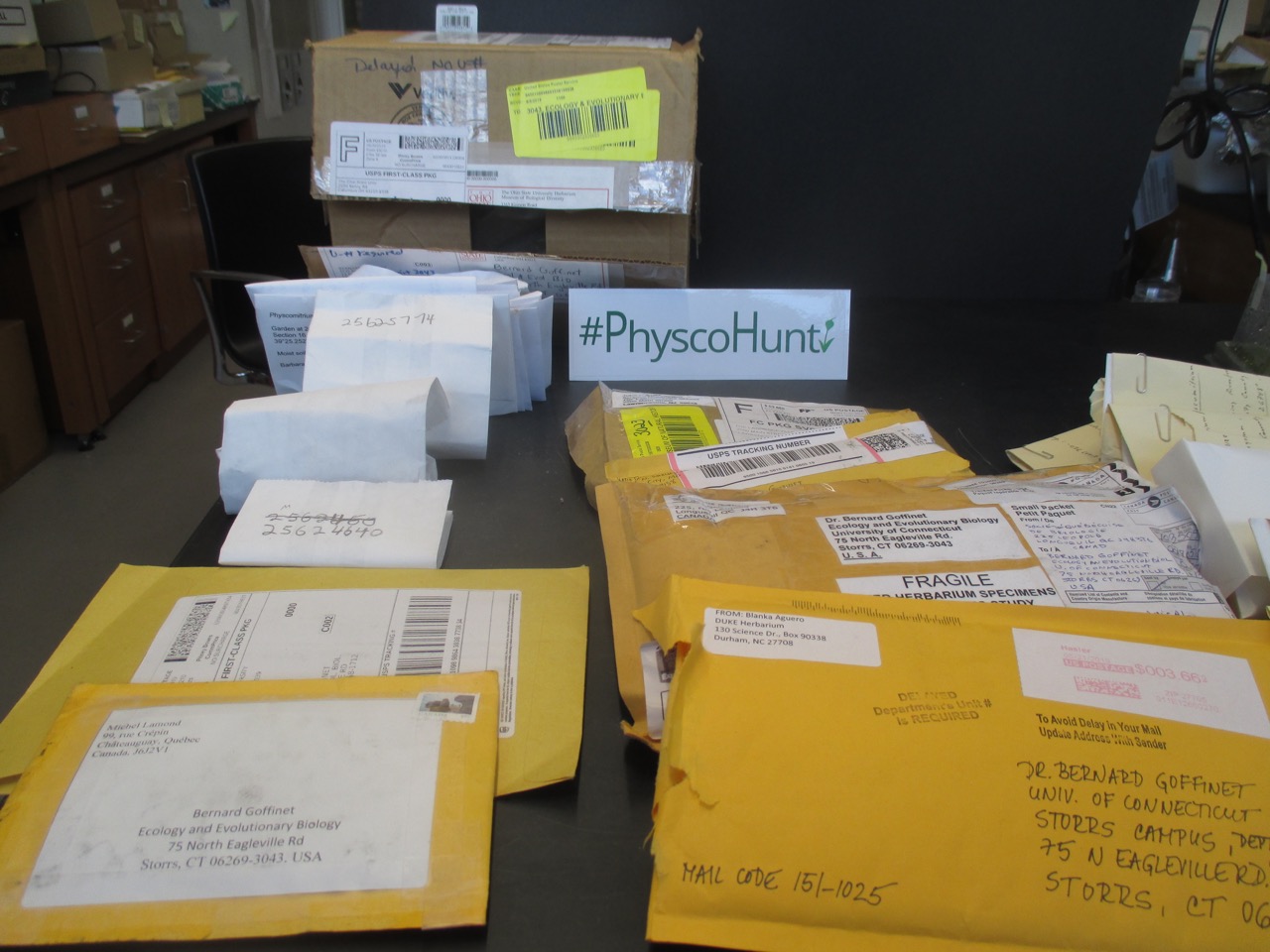

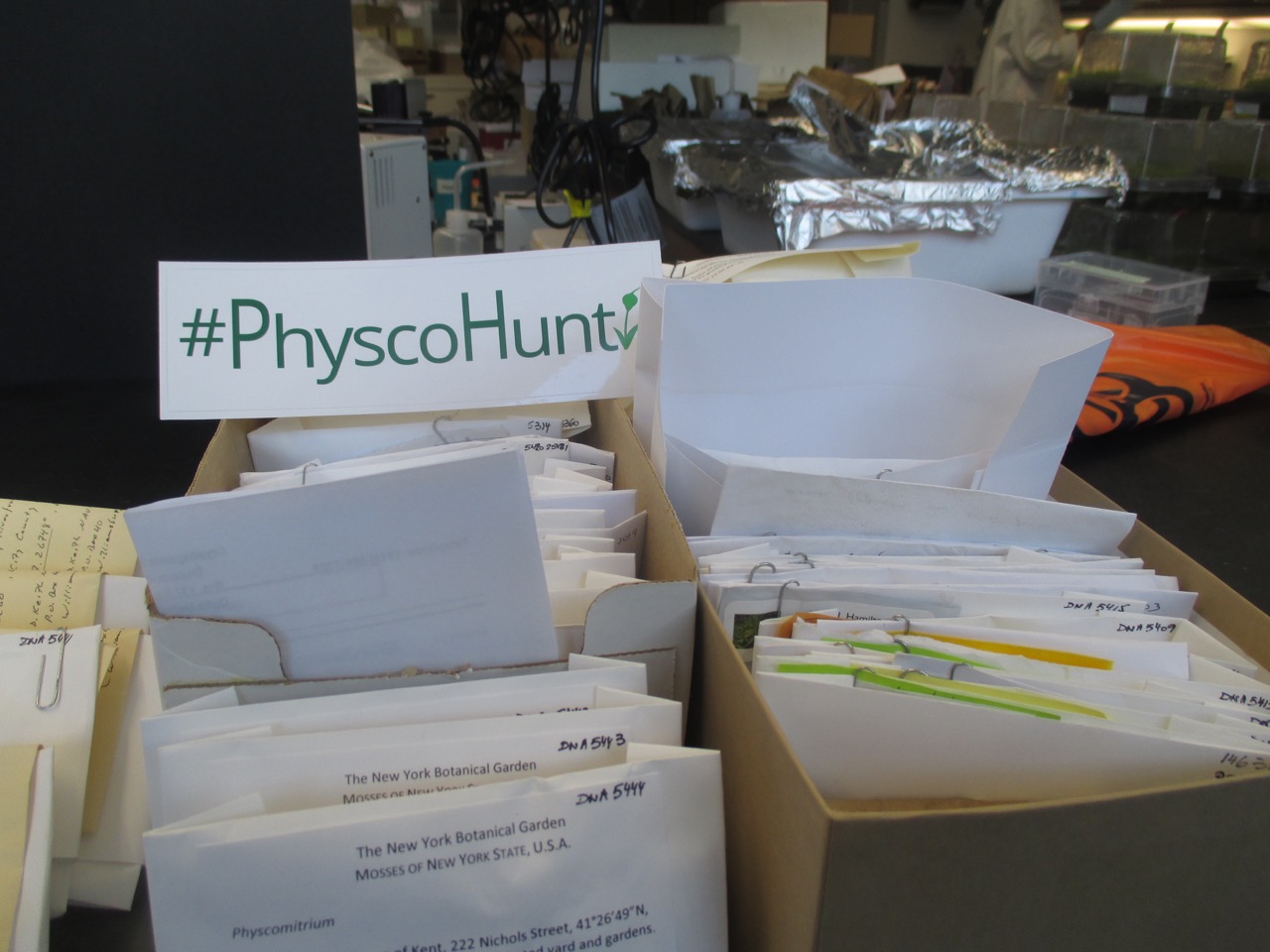

Our lab at UCONN received about 120 Physcomitrium samples directly from you. Every single sample that we received (even if we could not culture their spores) has become a scientific specimen of the CONN herbarium (publicly available for all researchers). This means it can always be used in future studies to investigate its morphological traits or re-extract genetic material. These vouchers will still be very useful in the imminent taxonomic studies.

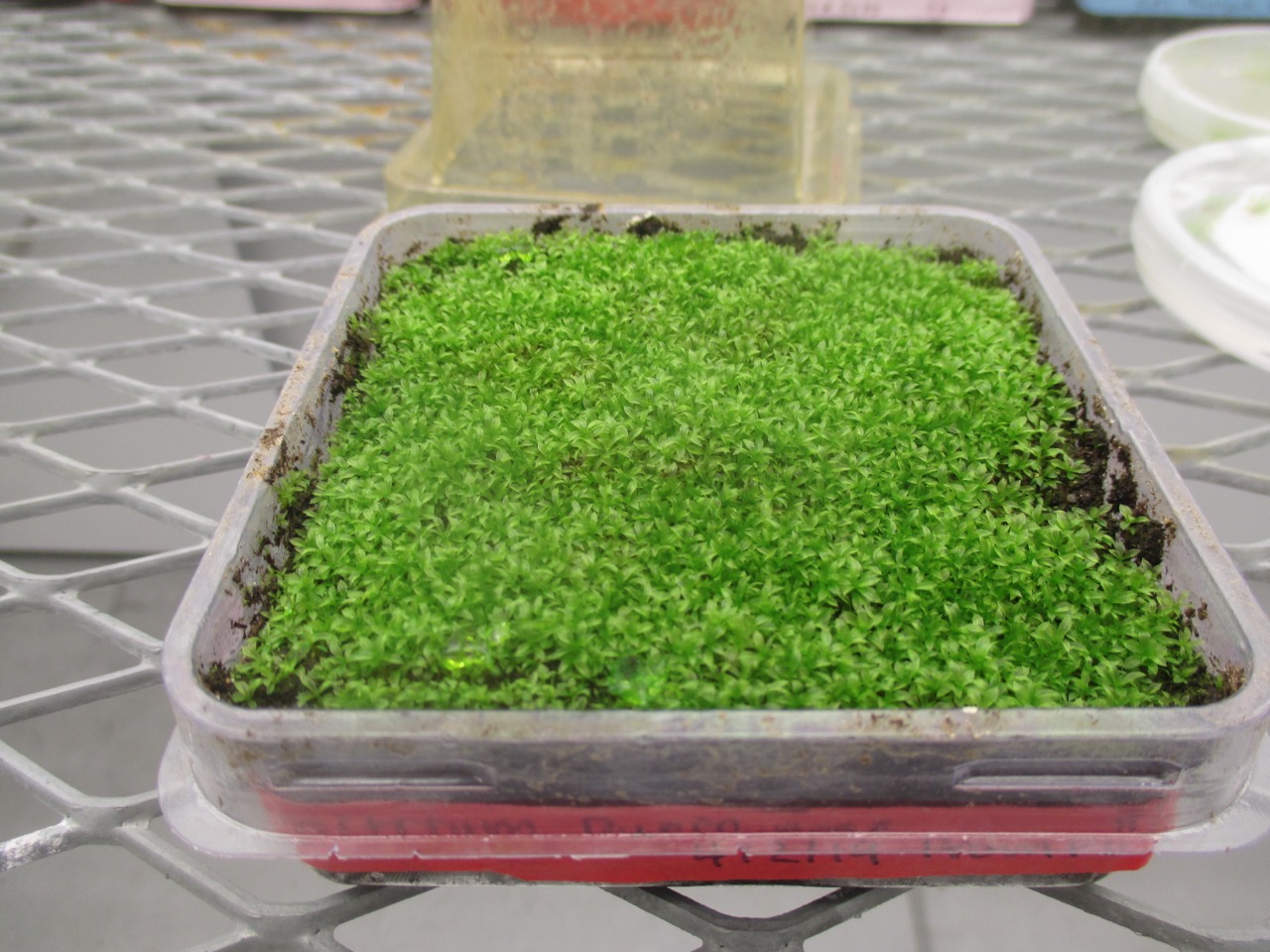

The next step of the process was to recover some spores and culture them. Not all spores made it into this last step for different reasons. For example, we realized that sometimes capsules would open during shipment, and maybe you realized that we modified the flyer last year, precisely to take this into account. Once that the cultures had grown enough, they were sent to the team at Texas Tech to sequence up to 600 genes from each of the accessions. A total of 65 samples made it to this last step.

Results overview

Although we will not be sharing here all the details of our research yet, there are a couple of relevant outcomes that we wanted to post on the project blog. These results have been already communicated in a couple of virtual botanical conferences during the summer (BL2021 and Botany2021). We also think that, as iNaturalist users, you are mostly interested in knowing what have we learned about these organisms that you collected growing on your backyard (sometimes, quite literally).

One name, several species

One of the original hypotheses of the project has been validated by our results. There is a lot going on under the umbrella name "Physcomitrium pyriforme". It is definitely one of the easiest mosses to identify and spot, but it turns out that it is not just one moss. We have detected that in Eastern North America there are at least three distinct goblet moss species (haplotypes) coexisting. Up to date, they seem to be morphologically indistinguishable (these are called "cryptic species"), but the truth is that nobody in recent times has attempted to discriminate different species within this complex. Notably, Elizabeth Britton (1858-1934) already proposed a taxonomic treatment of North American goblet mosses splitting what today we call Physcomitrium pyriforme into several taxa. Her approach was ultimately abandoned, but maybe she was at least partially right. We will hopefully know sometime soon.

Coexistence in sympatry

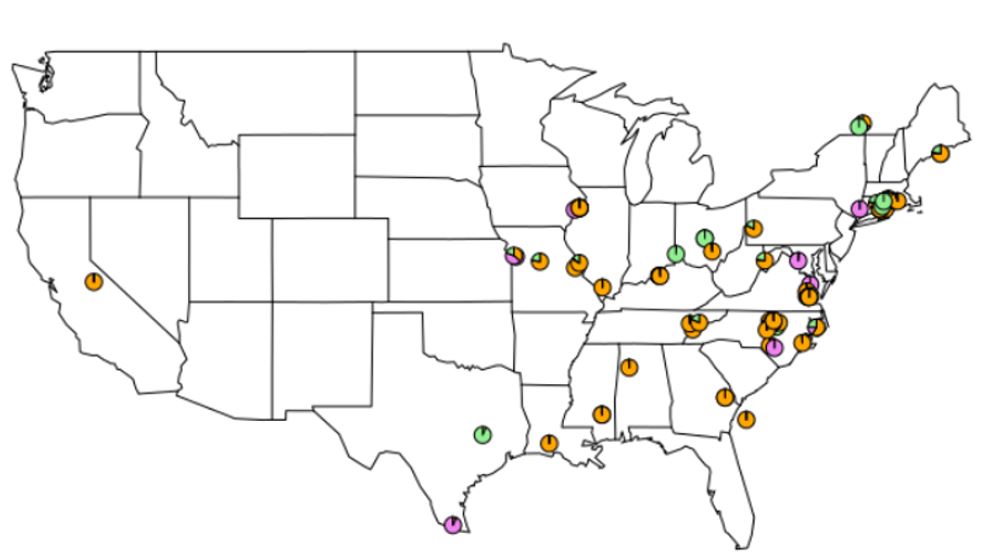

One of the most intriguing implications of the results we are obtaining is that the three hidden (potentially cryptic) American goblet moss species do not show a strong geographic pattern. It seems that within the Eastern United States, the three of them are potentially present in your area, regardless of whether you are in Vermont, Ohio, or Alabama. This was definitely a possibility we expected, but perhaps not the most straightforward, since speciation events are often facilitated by geographic isolation. We cannot discard that the three species, although present in the same areas, show other type of ecological niche specialization (for example, microecological conditions) but we can't be sure yet. These lineages do not remain unchanged, we have detected that some degree of admixture is quite common, but still, the three lineages seem to have their own proper distinctiveness, same as different oak species hybridize, but they keep their own distinctiveness.

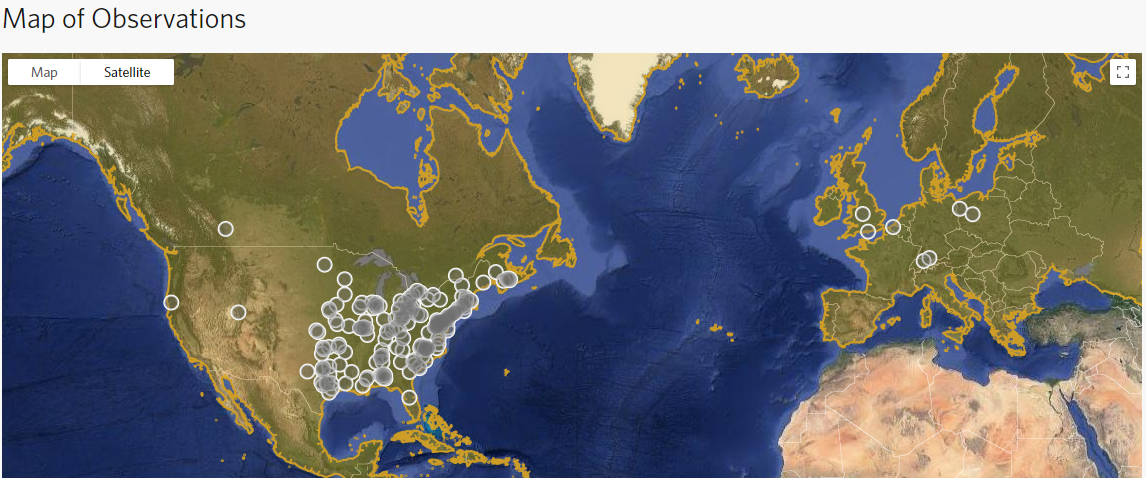

This maps show as circles the goblet moss specimens we have used in our study. The different colors (pink, orange, and green) represent the different haplotypes (potentially cryptic species) we detected. Circles with different colors represent samples that had some degree of mix of the different haplotypes. It seems that all haplotypes can be found across the latitudinal and longitudinal gradient of goblet moss distributions. There are areas with a lot of overlapped specimens and they always have the three haplotypes present. Remember that even if you can't see your location on this map, your sample is vouchered as a herbarium specimen. (Image prepared by Lindsay Williams)

A tangled family tree

As we said, polyploidy research was one of the targets of the project. The whole genus Physcomitrium has species with different genome sizes and chromosome numbers, suggesting that their genomes are not static. One of the sources of polyploidy is hybridization, which is extremely common in flowering plants, but an overlooked mechanism in mosses. Our research joins new discoveries from bryology that show that polyploidy might very well be a universal driving force of plant evolution, regardless their size and complexity. In particular, we have detected that several Physcomitrium species have a hybrid origin, and sometimes the parental lineage corresponds, or seems very close, to one of the Physcomitrium pyriforme lineages we mentioned above.

Further steps

We plan to continue our research with goblet mosses and try to resolve some of the pending questions. In particular, we need to verify whether the three cryptic species are indeed cryptic or whether they have some subtle but clear morphological characters that can be used to tell them apart. Also, our sampling did have a clear bias towards Eastern North America. Although Physcomitrium pyriforme mosses are present in Europe and Western North America, the amount of observations and samples coming from these areas is lower and we still need to determine how many (and which) genetic profiles are present there. It seems that goblet mosses will continue teaching us how these small plants evolve and diversify.

Once again, we are very thankful for your support and contribution to this project. We hope next time you spot Physcomitrium or other mosses you are more aware of the hidden diversity that surrounds us everywhere.