Vexing Vachellia: Ant "Acacia" in Costa Rica

According to the Missouri Botanical Garden's online Manual de Plantas de Costa Rica (see the Vachellia key), there are six species of Vachellia in Costa Rica: three obligately associated with "aggressive ants" (V. allenii, V. collinsii, V. cornigera) living in the stipular spines and three lacking mutualistic ants and the associated hollow spines (V. farnesiana, V. guanacastensis, V. ruddiae).

Since most "ant acacia" observations are just of leaves and spines, the nectaries on the leaves are the easiest way to tell these apart. Typical nectary traits for these species are:

Vachellia allenii (above) has many (up to 10), small, round nectaries at the leaf base. Note that they don't touch each other.

See also these V. allenii leaves and these V. allenii leaves.

Vachellia collinsii (above) with few (2-4), larger, round (pore-like) nectaries at the leaf base. Note that they often fuse together.

See also this V. collinsii observation.

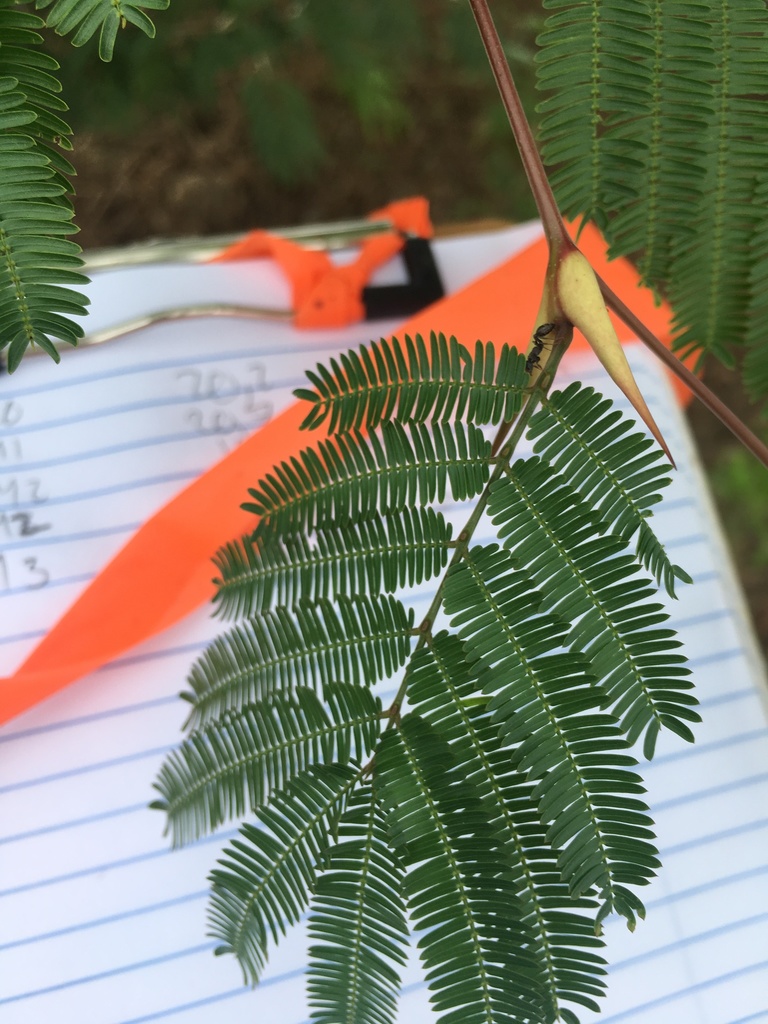

Vachellia cornigera (above) with solitary, large, elongated (slit-like) nectary at the leaf base.

The Ant Acacia Details:

Vachellia allenii only occurs in "very moist" forests, and has flowers clustered in ball-like heads.

Vachellia collinsii and V. cornigera -- both "bullhorn acacias" -- are the tricky pair. They are less picky about habitat (forests from dry to very humid), both have their tiny flowers in fat, finger-like spikes, and they can be found in some of the same areas.

Vachellia collinsii: Groups of nectaries at the leaf bases. Round, pore-like nectaries are set in rounded raised areas at the base of each leaf (on the petiole) and are generally in groups of 2-3 (sometimes more; ocasionally just one if the leaf is young and small). There are sometimes small nectaries along the leaf rachis where pairs of pinnae connect, but it seems to be less common in this species than in the other two.

Individual leaflets have palmate venation: two main veins meet at the base of the leaflet. (This trait taken from the Flora de Nicaragua description).

Fruit (legume) with a short, less than 1 cm beak at the tip, spliting open along both sides when ripe.

Vachellia cornigera: Solitary nectaries at the leaf bases and along the rachis where pairs of pinnae connect. Elongated, slit-like nectaries are set in elongated, raised areas along the petiole and rachis. Usually, only one nectary at the base of the leaf (on the petiole), occasionally another small one nearby if the leaf is large.

Individual leaflets have pinnate venation: there is only one main vein running out from the bade of the leaflet. (This trait taken from the Flora de Nicaragua description).

Fruit (legume) with a long, 1-3 cm beak at the tip, and indehiscent (never opening) even when ripe.